The world feels a bit … cold these days, and it’s not just winter’s doing. So, here’s some heart-warming news. A partnership between Mikinakoos Children’s Fund and Canadian ethical outerwear company Wuxly Movement will see 230-plus winter parkas donated to youth from 15 remote First Nations throughout Northwestern Ontario. We spoke with Colleen Martin, chair of the board of directors for the fund, to find out more. —Noa Nichol

Hello Colleen; please tell us a bit about yourself to start.

I have lived and worked in northwestern Ontario my whole life. My first encounter with First Nations people was through employment with Nishnawbe Aski Nation, which is the political organization advocating for rights and needs of First Nation communities in northern Ontario, including the same area Mikinakoos serves. That experience brought an awareness of the many injustices inflicted on Indigenous peoples for hundreds of years in Canada. Since that time, it has been my mission to bring awareness to other Canadians, including ways in which to reach out in reconciliation and peace.

What is the Mikinakoos Children’s Fund? When was it launched, and what is its aim?

Mikinakoos was created to address poverty by providing basic amenities, such as food, clothing, and shelter to First Nations children residing in remote First Nation communities. Mikinakoos was granted charitable status on August 21, 2014. Our vision is a world where every First Nations child is lifted from poverty and lives the good life as described by First Nations teachings.

Great news about the partnership between Mikinakoos and Canadian ethical outerwear company Wuxly Movement; what does this pairing entail, and why is it crucial now?

Culturally centred land-based learning reconnects Indigenous youth to the land and all that is good about their culture. During this time, when Canadians are struggling to understand the injustices they are only just learning about, particularly in regards to the long-lasting impacts of the residential school system, it is important for the youth to hear and experience that their culture is not “bad” or “evil,” as their family members were forced to accept in the past. The seven grandfather teachings and connection to the land are sacred and deeply important to walking in a good way. Youth are learning to understand it is good to be Indigenous; Canada was, and in many instances still is, wrong!

How will the donated winter parkas help youth in 15 remote First Nations throughout Northwestern Ontario?

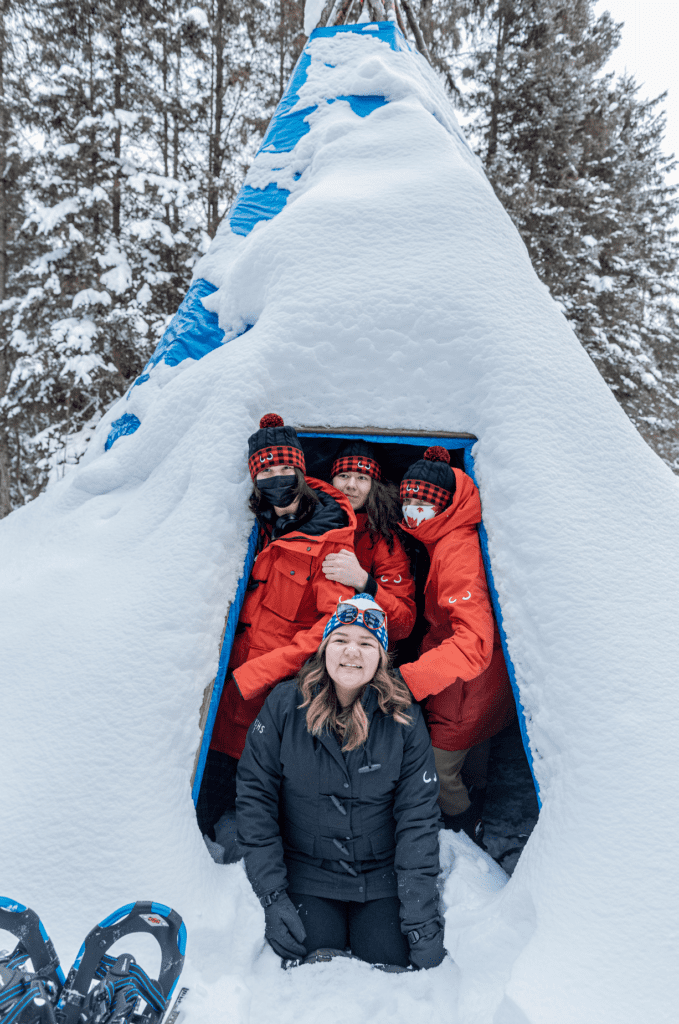

This wonderful gift from Wuxly Movement could not have come at a better time as far as the weather is concerned. This morning in Thunder Bay, Ontario, where I sit, it was -41 degrees Celsius. Further north, it was likely much colder. With this specific donation, Wuxly Movement has provided protection from the elements needed for high school students to participate in land-based learning with Elders and other teachers in their communities.

What (other types of) challenges do these youth face?

I might write a novel if I get started on the other challenges these youth face daily. First and foremost, their communities are chronically under-funded by the Indigenous Services Canada programs, which should meet the treaty commitments to Indigenous peoples made over a hundred years ago. Houses are seriously overcrowded; basic community infrastructure is in many cases rundown and outdated. There is no sewer and clean water in some communities and, even though a community might have these structures, there remain 61 boil-water advisories in First Nations communities across Canada after many years of government promises to rectify the more than 100 existing for decades. Recently, three young children, all under the age of 10, died in a house fire in Sandy Lake First Nation because without proper equipment the fire hydrants and fire truck water systems were frozen. Friends and family watched helplessly as the fire burned. In the current pandemic crisis, impacts to Indigenous communities are once again magnified. How do you isolate and protect your family in a home with two or three generations, 10 to 15 people, living in a two-bedroom home? This overcrowding also impacts the youths’ ability to perform well in school, where do you go to focus on homework? And even if you do well in school what are the opportunities in your remote community where unemployment is 90 per cent plus. Until very recently, federal and provincial governments argued over who should pay for health care and this situation left a young boy in hospital for two years when he could have spent some of his short life at home with family. Education and social services, as demonstrated by the recent successful human rights complaint, both remain underfunded. Why is funding to support a child on reserve less? A young girl from Neskantaga First Nation who was evacuated to Thunder Bay to live in a hotel for weeks as Christmas approached was concerned about Santa finder her. Her public statement on a news clip was: “All want is to go home. Why can I not have clean water like every other child in Canada so I can go home?”

Has the pandemic created new barriers/challenges for remote First Nations communities like the ones benefiting from this partnership?

The pandemic has magnified the challenges within communities in the region terrified of the impact should COVID-19 take hold. With 10-15 people living in one- and two-bedroom houses, the ability to isolate from the virus is next to impossible. One community, Bearskin First Nation, was in the news recently when more than half of their community members tested positive for the virus, putting a strain on local services. Many homes were running out of wood and water until neighbouring communities ski-dooed over with assistance. Imagine running out of wood when it hits your home and the temperature outside is -30 degrees Celsius or colder. Any other community would have seen the army deployed, Bearskin received six rangers from the federal government, three of whom lived in the community.

How else can Canadians help?

Canadians need to take the time to educate themselves on the injustices of the past and present and how the impacts are multi-generational, then they need to take the time to listen to First Nations people and communities about their challenges and what they see as their needs. Rather than telling First Nations what we can do for them, ask what is it you need that I could contribute to make a difference for you? Mikinakoos is struggling with this exact concept at the moment, as a grantor is asking for a list of items Mikinakoos would buy for an initiative to create opportunities for physical, arts, music and other activities for youth. Mikinakoos’ approach is to obtain the funding and then go to the various communities to ask what their needs are in order to respond. Everyone needs to start thinking outside of the box to respond to community needs; don’t send hockey skates if the community has no rink, don’t fund a baseball league when a community has no coaches, don’t send tofu, which is culturally unaccepted, and no-one has any idea how to prepare it … you get the idea.

What would you like readers to know about the Country’s remote First Nations communities, and the youth/individuals who live in those communities?

All the community members I have met only want prosperity and happiness for their community and especially for their children—and seven generations of children. First Nations culture considers the impact of decisions on seven generations, perhaps that answers the question of why environmental impacts are so important.

February 6th, 2022 at 10:41 am

Way to go Colleen!