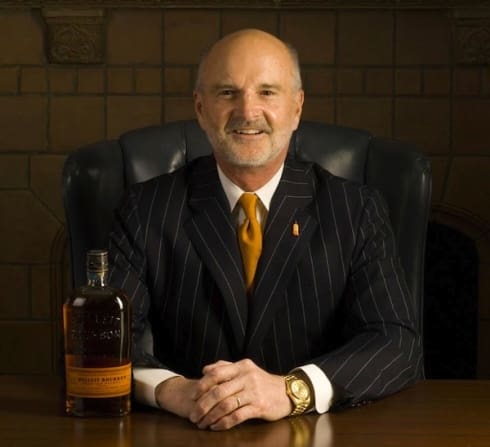

Tom Bulleit will joke that he merely inherited a great last name and an even better bourbon recipe, but the man who established Bulleit Bourbon as the brash, award-winning brand we know today has bourbon in his blood.

Legend swirls around his family’s high-rye frontier whiskey, but one thing we know for fact is that the recipe came from Bulleit’s great-great-grandfather Augustus, and was lost for more than a century after Augustus disappeared on a supply run as he traveled up river to New Orleans, just before the onset of the American Civil War.

No one knows what fate befell Augustus, but in Tom’s hands his bourbon recipe has been reborn, and Bulleit is now the fastest growing bourbon brand in America, the top-trending American whiskey (according to the World’s 50 Best Bars poll) and the preferred bourbon of Deadwood’s Al Swearengen himself.

Bulleit was up from Louisville, Kentucky, to talk about his three labels—Bulleit Bourbon, Bulleit Rye and the silken Bulleit Bourbon 10 Year Old—and we sat down with the modern-day whiskey baron to learn more about his family history, tasting tips, and the whiskey in the jar, oh. —Kelsey Klassen

How do you get the most out of your whiskey tasting?

The primary methodology that I learned a long time ago from my friend Pete Gunterman, a chemist and educator who literally grew up down the street from me in Louisville, and went on to be the chief training officer at the House of Seagram. Seagram’s a big house—when we got together with them in 1997 they were the largest distiller in the world by far—and he trained master distillers. And his methodology was what he called “organoleptic analysis”.

The word organoleptic as I understand it—I can’t spell it, but as I understand it—means an analysis of the senses. So you’re going to look at the colour of the whiskey, the nose of the whiskey, the taste of the whiskey.

His technique is to hold the glass in front of your face and open your mouth and breathe in. Then you’re going to take a little sip, and that’s going to clear your palate. And then your second sip really is what the whiskey tastes like, and you’re going to breathe across your tongue to get the full taste of the whiskey.

Following that, I think it’s really important to put a little water. It doesn’t have to be as subtle as scotch. These are 90-proof whiskeys,—45 ABV—so you can add some water to it, maybe 1:3 or 1:5. And what that will do is really open them up, just like a wine opens up with oxygen. Quite literally, there is a molecular change, a chemical change in the whiskey. You can literally see the oils in the whiskey rising to the top of the glass.

What gives whiskey its colour?

It’s a completely natural product, so all of the colour comes from the char on the barrel. You can’t add any colour to Kentucky straight bourbons.

What are the flavours you can expect in a bourbon?

I always like Bill Samuel’s explanation of Bourbon: Bill ran six different distilleries and we used to have bourbon-scotch debates. The scotch fellows can go on about the ‘amber waves of grain’ and the ‘water washing up on the Sottish shore against rocks that have been there since the Norman invasion’. I mean, they go on and on. [laughs] So Bill Samuels was in one of these debates, and they said, ‘Well, Bill, tell us what bourbon tastes like? Tell us about bourbon.’ And he said, ‘Well, it pretty much tastes like bourbon.’

An extremely pragmatic sort of Kentucky approach. [laughs]

But I think the flavours you’re going to get are interesting. You’re always going to get some vanilla; the vanilla and the sweetness is going to come from the sugars that are in the barrel itself after the char of the barrel. You’re certainly going to get a lot of spice with Bulleit. From there, you’re going to get a sweetness and a lightness with Maker’s, for instance. Knob Creek has a sort of nuttiness to it. What I think is interesting about the flavour profiles is every one is different.

How did you find the recipe that you wanted to make and what made it different than what the other distilleries were making?

Well, the recipe that I had always wanted to make was Augustus’ recipe. And that was passed down from Augustus to John Joseph, to F.A (Francis Aim), to my father Thomas, to me, and to my son and daughter, Tucker and Hollis. And I didn’t think, ‘Oh boy, this’ll be drier, or spicier.’ You just made what you were passed down to make. That only occurred to me about three years ago. You know, well why didn’t you do this or that? You have no idea if it’s going to be good or bad, it’s just the family recipe. Like the Beams make what Jim Beam made 150 years ago. Jack Daniels makes what what Jack Daniels made.

And there’s a lot of history that goes a long with it. For instance, in Kentucky in the year 1800 there were 2,000 stills in Kentucky. It was a function of our agrarian society. By the time you get to 1900 you have 200 stills. By the time you go through Prohibition, the Great Depression and through the Second World War, where a lot of the plants made medical alcohol, and come all the way out the other end to where we are, I think we are building the 12th distillery, now, in Kentucky.

Why did you love bourbon in the first place and want to bring the recipe back?

Well, when I was growing up I was working in the [Louisville] distilleries. This was a long time ago when there were hundreds of people who worked at the distilleries. It was a fascinating industry; back then, if you wanted to get the temperature off a chart there was somebody sitting there on a stool all day. It’s done with computers now, but very little has changed.

And really, I kind of grew up in it. If you grew up in the distilling families in Louisville and Bardstown, it’s just sort of what you know. Like the fishing industry is here.

America has the trifecta of jazz, blues and bourbon that it can claim as its own. Is there a lot of pride in the product?

Absolutely. It’s what we call the American spirit. It is literally the only spirit that is unique to America, to my knowledge. You can make bourbon any place in America, but it’s like Champagne—you have to make it in America. And if you make Kentucky straight bourbon it has to be made in Kentucky. It is absolutely domestic product, and it’s primarily driven by corn, which goes back to maize, which goes back to the native Americans.

Be the first to comment